Des lois et des lacunes : ces enfants qui travaillent au Cameroun

12 June marks the World Day Against Child Labour. The aim of this day is to raise public awareness of the alarming situation of children forced to work throughout the world.

According to the World Labour Organisation, children are defined as those aged between 5 and 17. However, statistical bodies such as the World Bank and Cameroon's National Institute of Statistics tend to focus on the 5 to 14 age group, as this is the age limit for compulsory schooling.

Where are those invisible little hands that carry out all sorts of tasks?

By 2022, UNICEF, the World Bank and the International Labour Organisation estimate that 160 million children will be working at least one hour, or even full days.

Alarmingly, 28% of working children aged 5 to 11 and 35% of those aged 12 to 14 are not in school.

But what is even more worrying is that 79 million of them are involved in dangerous activities, or even the worst forms of work such as slavery, prostitution or enlisting as child soldiers.

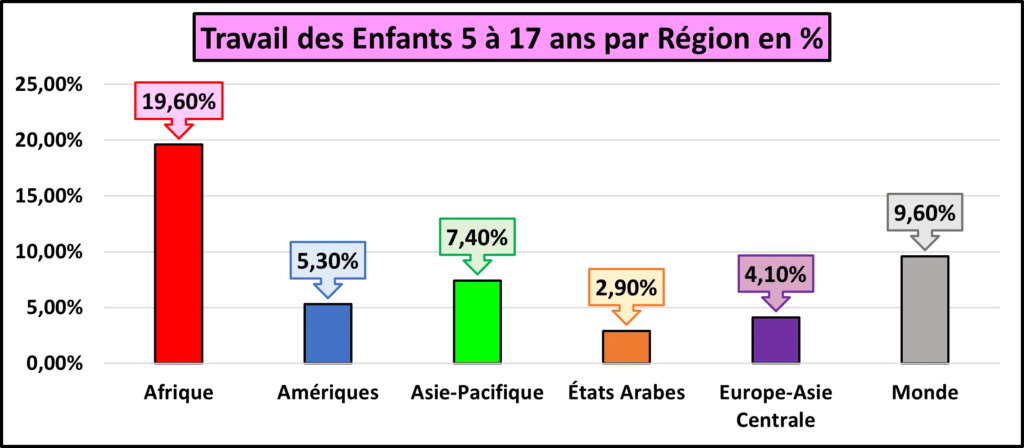

Contrary to what we hear in the media when tragedies occur, the majority of them are not in Bangladesh, India or Asian countries. The table below tells a different story.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the demographic explosion has brought an additional 16.6 million children into the labour market over the last four years.

What encourages children to enter the labour market?

The first reason that springs to mind is, of course, poverty.

In Africa in general, and in Cameroon in particular, the impact of poverty is greater in rural than in urban areas. When parental resources are low, child labour becomes an indispensable necessity to stay, at least, at subsistence level.

Although the Cameroonian government ratified the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in 1993 and incorporated it into its Labour Code: "No child shall be employed in a business before the age of 14" (Article 86) and school attendance has become compulsory up to the age of 14, the eradication of child labour is far from being a reality, even though the penalties are severe.

*RiddleWhich is the only country not to have ratified this convention? (Answer at the end of the article.)

These measures have certainly had a positive impact on working hours. The downside is that young people have to juggle school work and gainful employment, often to the detriment of their studies. The Ministry of Basic Education has drawn up the 2023-2024 school calendar, with 36 weeks of classes and 34h30 per week. In addition, on average, children do 11.40 hours of paid work per week. (World Bank)

What are the causes of child labour?

the banks

They should have played a crucial role in development.

Under colonial rule, the banking system focused on exports and trade in raw materials. They acted for the greatest profit of foreign companies. The population has always been excluded from this sector.

The crisis of 1980, which saw the failure and closure of many banks, led to significant financial losses, if not ruin, for households and businesses. The mistrust of Cameroonians still persists.

Access to credit

Half of the population will have a deposit account by 2021, and the split will favour mobile money providers over the formal sector.

The majority of small and medium-sized businesses are in the informal sector. They generate 35% of GDP and provide 70% of jobs. Yet they all suffer from poor access to credit.

The conditions for obtaining credit are stringent. You must have had a bank account for several years, have a stable and constant income, have a guarantee (deposit or mortgage) and have savings. All this is often inaccessible to small entrepreneurs. To cap it all, the credit rate is over 15% (2022). Businesses therefore resort to self-financing (76%) and informal short-term credit associations that require no collateral, such as Tontines (24%). However, these associations have been in the sights of the Treasury for several years.

Owning a business or land (e.g. farmland or forestry) tends to increase child employment in both rural and urban areas. Child labour becomes the best solution: learning "on the job" is more profitable than that provided by the costly education system, and it perpetuates the family business.

Education

It's true that primary school has become "free", but what about secondary and university education? The costs are high. It's a long-term investment, and opportunities in the formal sector (large companies) are highly uncertain. Low incomes lead parents to question the return on schooling.

Income shocks

A wedding, a dowry or a funeral are all events that weaken income but are generally absorbed through Tontines. But what about major medical operations? There is no universal social security cover and individual health insurance is too expensive.

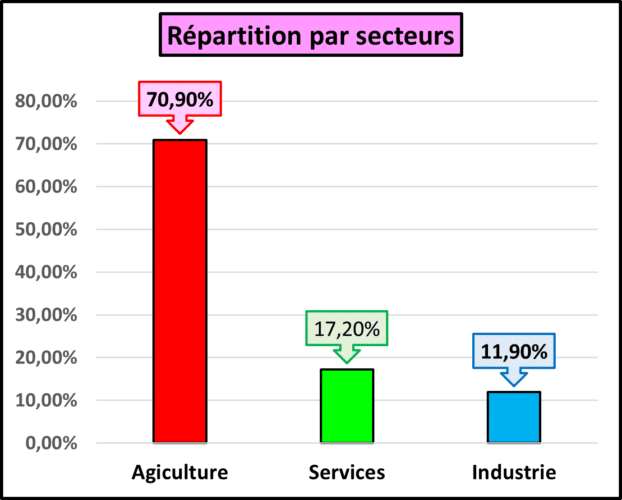

The table below is revealing:

The risks of impoverishing and catastrophic spending have a terrible and above all lasting impact on household incomes and their ability to invest in their own future and that of their children.

does this justify the exploitation or child labour?

Our first healthy reaction is to say NO!

However, in the face of reality and in the light of the elements outlined, we can envisage extenuating circumstances for work, but certainly not for the exploitation of children. The uncertainty of the present and the unpredictability of the future are all factors to be taken into account. Is it possible to maintain a minimum standard of living today without jeopardising the future of children? It's a difficult equation.

For decades, the Cameroonian government and international institutions have been putting in place mechanisms to improve people's lives and reduce child labour as much as possible. These efforts are slow to bear fruit. To be continued ...

*Response The United States. Conservatives, essentially the Republican Party (Reagan, the Bushes father and son, Trump) are opposed to it because it would be contrary to the Constitution.